Pursuant to the Indofuturist intent of reclaiming diminishing aspects of Indian culture, Virtual Sanskrit Archive uses contemporary digital media technologies to reincarnate the ancient Sanskrit language in a fictional future. It uses an ancient Sanskrit verse as a subject, and within the narrative, as a subject for preservation. As the language may or may not be comprehensible in the Indofuture, in addition to speech, gestural performance is used to capture the essence and meaning of the archived verse.

This purpose of this artefact was to reclaim aspects of Indian culture that were lost through colonialism. This reclamation was also imagined as a means for celebrating the richness of Indian cultural heritage.

Inspired in part by Indigenous musician Jeremy Dutcher’s reclamation of the voices of historic Indigenous musicians, performing traditional Indigenous music in their native languages, stored in wax cylinder recordings. Dutcher’s restoration of a nearly forgotten history and a reincarnation of ancestral voices is an example of a decolonised restoration of a musical artefact. Using Dutcher’s reclamation as a creative inspiration, Virtual Sanskrit Archive was envisioned as an archival tool for the preservation of Sanskrit language in a speculative future. Virtual reality was chosen because of the potential for embodiment a virtual space could offer, and in how its affordances might be applied as a medium for archiving across generations. This artefact leveraged the notion of presence in virtual reality to metaphorically indicate being in the presence of the ancient language. Gestural performance was used to express the language beyond the words within the verse, making it reach people in more ways than one.

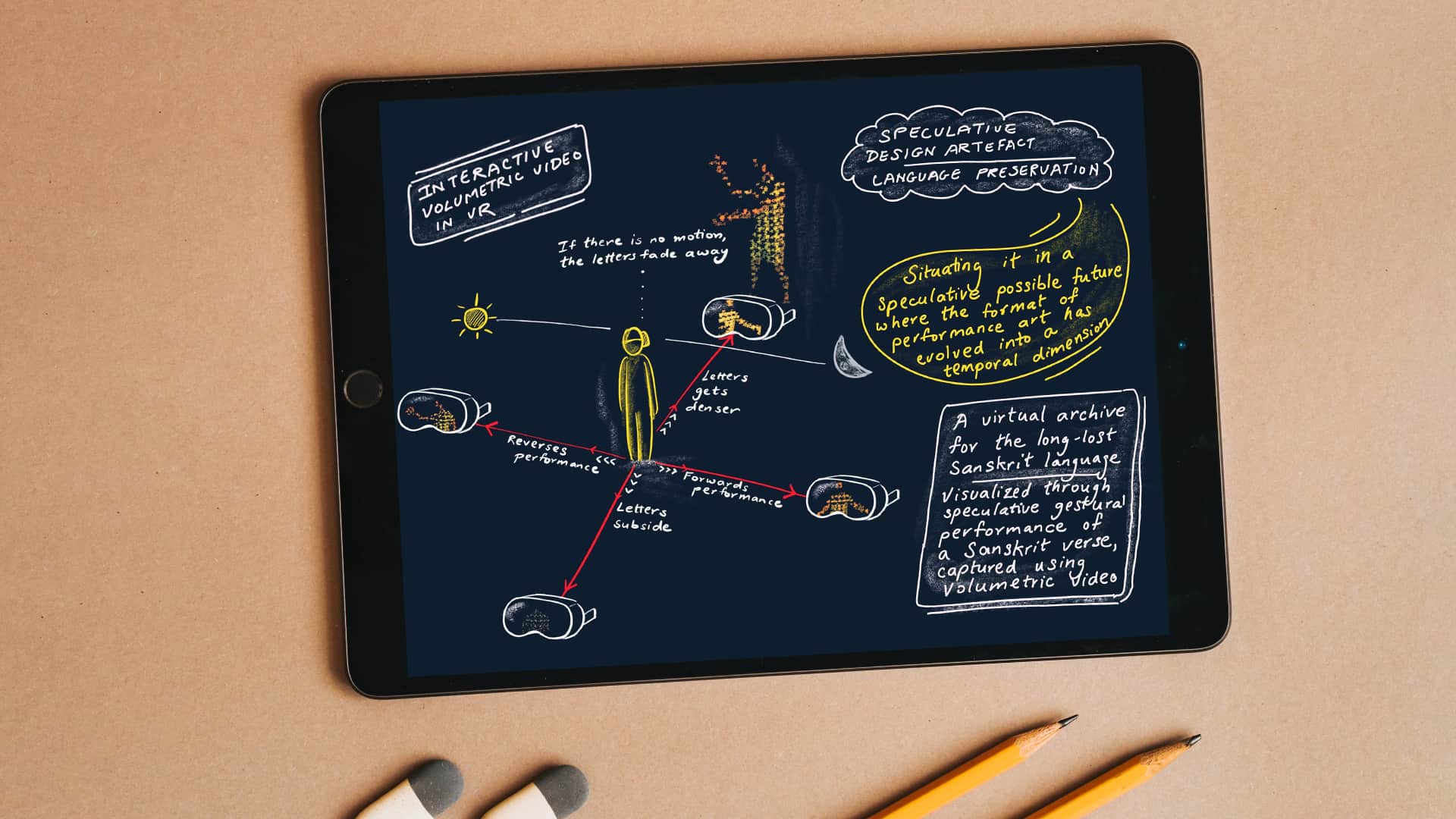

The wireframe visualised the setting of the performance video in virtual reality and gave an overview of the interaction with the viewer’s movement. As the viewer moved close to the performance video, the superimposed letters would intensify, and as the viewer moved away, they would fade, mirroring how the language needs to survive through consistent usage.

Construction

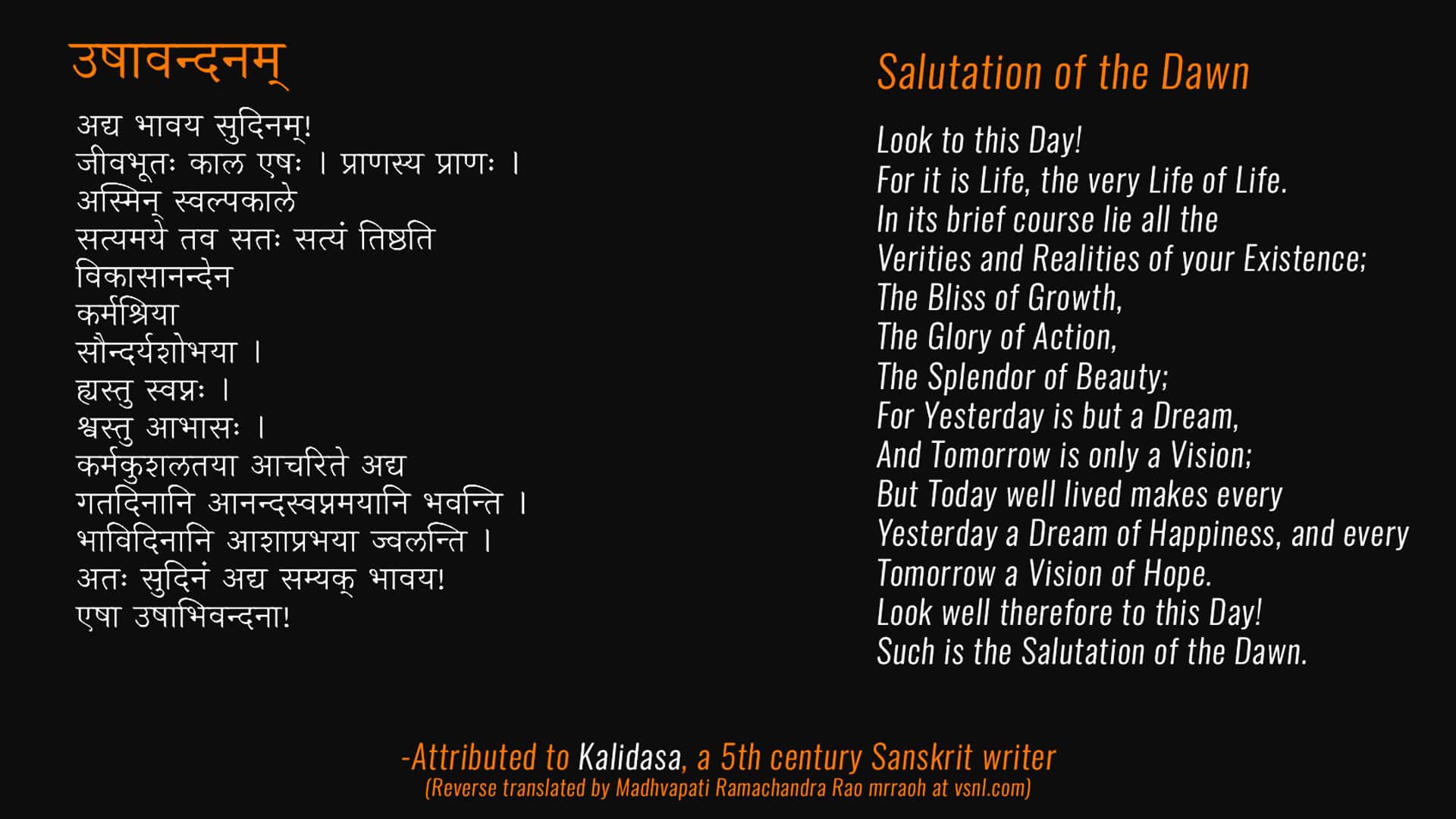

An ancient Sanskrit verse titled Usha Vandana (translates as “Salutation of the Dawn” in English), attributed to the 5th century writer, Kālidāsa was used as the subject for this artefact. In the artefact, the verse is spoken by my mother, Minal Bandodkar.

The gestural performance was captured using volumetric video and synced to the Sanskrit narrative in Unity3D (Unity technologies). Being in a pandemic lockdown, the first iteration of the prototype was a makeshift arrangement. Different types of representation of this data, such as points and sprites, were explored. The aesthetic that emerged from the exploration was a superimposition of Sanskrit letters from the verse onto the points of the character’s 3D mesh.

In order to activate Indian traditional art at every level this artefact was created in collaboration with Kathak performer, Tanveer Alam, who choreographed and performed several dances to the spoken verse. This second iteration with Alam was filmed in a studio setting. Volumetric data of Alam’s performance was exported from Depthkit to key out the background elements and the footage was brought into Unity3D.

Initially, an audio narrative of the verse was planned as being part of the experience. This feature was almost abandoned due to the lack of text-to-speech translators for Sanskrit. While discussing this project with my mother, she volunteered to recite the verse in Sanskrit as well as she was able to, as her command of the language is not exact. Her recitation of the verse went on to be integrated into the artefact. Comparing my mother’s level of familiarity with Sanskrit with mine made me realise how the presence of this language is indeed depreciating with each generation, and that archiving of Indian art and culture is particularly important in a digital world that does not put non-white voices front and center. The use of my mother’s voice for recitation of the Sanskrit verse, in turn, opened a new avenue for probe: the role of intergenerational knowledge-sharing that might serve as a cue for speculation for viewers of this Indofuturist world.